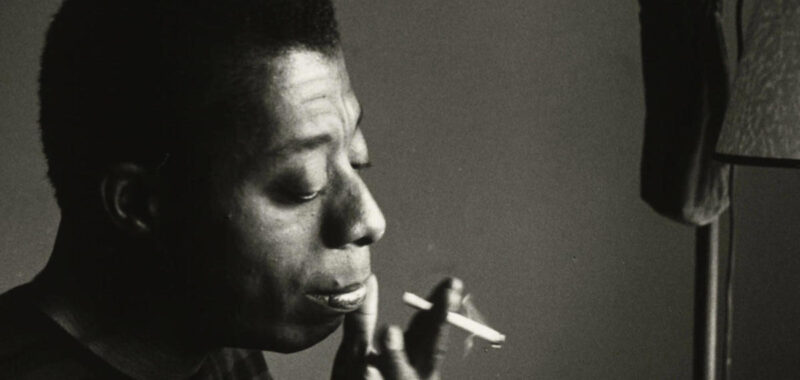

In 1965, in the packed Cambridge Union Society in London, James Baldwin, a voice of the civil rights movement, debated the commentator William F. Buckley, who was skeptical of the cause. The motion: that “The American Dream has been achieved at the expense of the American Negro.”

Baldwin said, “It comes as a great shock around the age of 5, or 6, or 7, to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you.”

Baldwin won the debate in a landslide, 544 votes to 164.

“He didn’t go to college, he ain’t educated, he’s po’ – he grew up in a place that isn’t supposed to be able to hold fire with Buckley, [or] with anyone,” said Kevin Young, director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., and poetry editor at The New Yorker. “That’s what’s so tremendous about him, is his almost very American transformation to say, ‘I have a voice, and I know what I believe, and I can say it beautifully.'”

One-hundred years ago, James Arthur Jones was born in Harlem, New York. Soon after, his mother, Emma Berdis Jones, married David Baldwin, a volatile Baptist preacher. Her son, now called James Baldwin, found a nearby escape: the 135th Street branch library, which he visited at least three or four times a week.

Baldwin once said he read every book in the building, which is now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Barrye Brown, curator of a new exhibition dedicated to “Jimmy” (as he was known), showed “Sunday Morning” a yearbook in which Baldwin wrote that he wanted to be a novelist and a playwright. “It seems like he knew that he was destined for great things!” Brown laughed.

In 1948, at the age of 24, Baldwin moved to France, where he wrote his first novel, “Go Tell It On the Mountain,” and his first collection of essays, “Notes of a Native Son.”

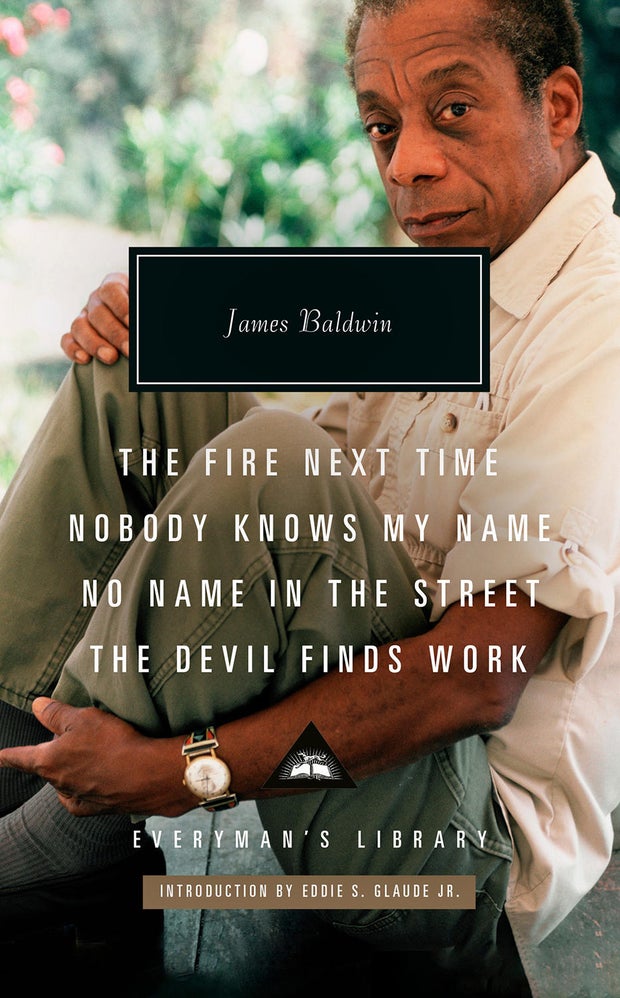

Everyman’s Library

Rhea Combs, who curated the Smithsonian’s new National Portrait Gallery exhibition on Baldwin, said, “There was this shadow that always was sort of cast over him. He was a visionary, a visionary thinker, and sort of speaking truth to power in a way that it was not necessarily always sort of recognized or appreciated at the time.”

In the 1960s, Baldwin marched and spoke out for civil rights in Selma, in Washington, and elsewhere, acquiring a reputation as an oracle for the movement. “He’s doing that civil rights work that led in many ways to the movement,” said Young. “He transforms his unease into writing.”

Combs said that Baldwin, at heart, was an integrationist, “who really sort of believed that there were these opportunities for America to live up to her principles and values. He’s using his writings as a way to be autobiographical, but it becomes a portrait of America ultimately.”

Baldwin’s books and essays reflect many facets of who he was – Black, New Yorker, expatriate, homosexual. Combs said the fact that Baldwin was gay was not widely known, but presumed through the text of his work. “James Baldwin is a multiplicity of identities, just like we all are, and that’s what I think resonates so much with his writings, is that grappling of these multiple selves that make up an individual,” she said.

In 1956, he published a pioneering novel, “Giovanni’s Room,” about a love affair between two white men in Paris. Young said, “I always go back to this quote: ‘I want to be an honest man and a good writer.’ As a man, he wants to be honest. And as a writer, he wants to be good. These are slightly different things!”

James Baldwin died in 1987 at 63 at his home in the south of France, which was paid for by his 42 books and hundreds of essays.

Baldwin, whose own grandmother had been enslaved, became one of our most history-based writers, according to Young. “You can’t get to America without going through Baldwin,” he said.

Sanneh asked, “If he were still with us, do you think he would be surprised at how many people are still reading him, and still talking about him?”

“It depends which Baldwin you meet,” laughed Young. “I think maybe in public he’d be humble, and then in private say, ‘I knew I was right,’ you know?”

READ AN EXCERPT: “The Fire Next Time” by James Baldwin

For more info:

- Exhibition: “JIMMY! God’s Black Revolutionary Mouth,” at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Harlem (through February 28, 2025)

- Exhibition: “This Morning, This Evening, So Soon: James Baldwin and the Voices of Queer Resistance,” at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C. (through April 20, 2025)

- Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, D.C.

- James Baldwin Digital Resource Guide (Smithsonian)

- “The Fire Next Time; Nobody Knows My Name; No Name in the Street; The Devil Finds Work” by James Baldwin (Everyman’s Library), in Hardcover, available via Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Bookshop.org

- JamesBaldwinBooks.com (Penguin Random House)

Story produced by Mary Raffalli. Editor: George Pozderec.